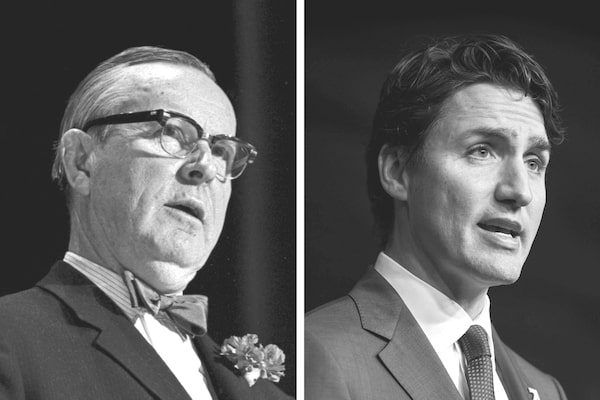

Today, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau finds himself in a similar position to Lester B. Pearson in 1965, Andrew Cohen writes.ERIK CHRISTENSEN/DARRYL DICK/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Andrew Cohen is a journalist, professor at Carleton University, author of Extraordinary Canadians: Lester B. Pearson and co-editor (with J.L. Granatstein) of Trudeau’s Shadow: The Life and Legacy of Pierre Elliott Trudeau.

On the night of Nov. 8, 1965, Lester Bowles Pearson watched his re-election with little joy. Always more diplomat than politician, he had finished the campaign weaker than he began, just like his three other campaigns as leader of the Liberal Party. That fall, once again, he was reconciled to governing without his much-coveted and much-promised majority.

Oh, it had been close this time. Very close. The Liberals won three more seats (131) than they had in 1963, when “Mike” Pearson became Canada’s 14th prime minister. Still, they were three short of a majority.

Mr. Pearson had believed his hawkish advisers, Keith Davey, national director of the party, and Walter L. Gordon, minister of finance. They trusted the encouraging polls, saw an opportunity, urged an early election. When it went bad, both resigned.

“The major issue of the campaign seemed to be whether or not Canada needed a majority government,” wrote Richard Van Loon, a political scientist. “It was an issue which apparently failed to quicken the pulse of Canadians.”

Rather than undoing Mr. Pearson, however, that election remade him. For the next two years, in league with the New Democrats, he would lead a transformative government. It would create modern Canada, turning the lisping, unassuming Mr. Pearson into the greatest prime minister of the postwar era.

By the time Parliament was spent in the spring of 1968, so was Mr. Pearson. Uninterested in contesting a fifth election in 10 years, content with his record and confident in his successor, he announced his retirement. He was 71.

Today, Justin Trudeau is in an eerily similar position. Like Mr. Pearson, he rebuilt a shattered party and led it back to power. Like Mr. Pearson, he called a snap election that gave him only two more seats, 11 short of a majority. Like Mr. Pearson, he has weathered scandal. Like Mr. Pearson, he faces a second minority government, navigating the shallows of a hung Parliament.

But in calamity, opportunity. If Mr. Trudeau learns from his mistakes, rallies progressives and puts policy before politics, he can do much. Rather than spending the next three years contemplating his place in Parliament, he can find his place in history.

For Mr. Trudeau, who once taught acting, another minority government is a chance to write the ending to his improbable drama, the dauphin of good looks and thin résumé who inherits the diminished Liberals in 2013. Critics call him a lightweight and a poseur of sunniness, socks and celebrity, and reliably underestimate him.

Then, two years later, he does something staggering: He outruns and outwits Stephen Harper’s Conservatives and turns his rump caucus of 36 into a majority of 184. Suddenly he is the saviour of the party, author of the Liberal Restoration, Canada’s boy wonder.

In office, Mr. Trudeau is erratic. He fulfills some promises, discards others and suffers self-inflicted scandals and missteps. When he loses his majority in 2019, as his father did in his second election, in 1972, the comparison is irresistible. Can Justin regain his majority, as Pierre did in 1974?

In 2021, Justin tries and falters. After a near-death experience in August, he shrewdly exploits the inconsistencies of the Conservatives. On Sept. 20, he salvages a second consecutive minority government with a historically small share of the popular vote (32.6 per cent). If Mr. Pearson was a strategist, Mr. Trudeau is a tactician.

Which leads to the third act of the stunning ascent, fitful stewardship and uncanny resilience of Justin Trudeau.

Now, though, the story is no longer how Justin Trudeau became Pierre Trudeau in 1974, survived and lasted another 10 years. It is how Justin Trudeau became Lester Pearson in 1965, succeeded and left.

************

Lester Pearson? In temperament, intellect and experience, could two prime ministers a half-century apart be more different? Mike was cerebral, enigmatic and shy. He was a soldier, a professor, a cosmopolitan, a Nobel laureate; as a diplomat, he was the best-known Canadian in the world. He was born a Victorian and raised an Edwardian. He looked so dull on television that he hoped to be judged by “the record, not a recording.” By 1968, he was passé, an antiquarian in the Age of Aquarius.

Born a year before Mr. Pearson died, young Justin was impulsive, adventurous and gregarious. He was a teacher, actor and outdoorsman, a dilettante. He loves politics and plays it masterfully; since arriving in Parliament in 2008, he has never lost an election. His tenure as Prime Minister, which began when he was 44, is already longer than Mr. Pearson’s, whose began at 65.

Funny thing about Mr. Pearson and the Trudeaus. Had Mike never been prime minister, nor might they. It was Mr. Pearson who made Pierre Trudeau in Ottawa. As his political godfather, he recruited him in 1965, named him his parliamentary secretary and then minister of justice, advanced his reforms in divorce, abortion and homosexuality and gave him license to challenge the Quebec separatists. And, quietly, he made him his successor.

If Pierre had not been philosopher king, would Justin have become crown prince? Would Justin have risen if his name were Justin Tardiff? And now, would he be channelling Mr. Pearson in this, likely his last act in politics?

Justin had tried being his father, the strong man and nation builder. It didn’t work. In 1974, after two years in minority championing an economic nationalism supported by David Lewis and the NDP, the Liberals engineered their own defeat in Parliament. The architect, again, was Keith Davey, who would now become the most gifted political strategist of his time. He loved Mr. Trudeau, as had Mr. Pearson.

Justin had no such eminence grise to check his impulses, a carelessness that brought him the Aga Khan, SNC-Lavalin, WE Charity, his ill-attired visit to India and the short, unhappy tenure of Julie Payette.

In 2021, another election, another misjudgment. Mr. Trudeau’s vanity project costs $620-million and ratifies the status quo. He is unapologetic. Resign? As Jason Kenney knows, that’s so 1960s.

Now Mr. Trudeau, in his third term as Prime Minister, eyes what Mr. Pearson did in his second. Between 1965 and 1968, Parliament produced a geyser of legislation: official bilingualism, universal health care, old age pensions, the guaranteed income supplement, a commission on the status of women, a federal labour code, student loans, collective bargaining in the public service, open immigration, the Order of Canada. Today’s Canada is Pearson’s Canada.

In his own time, Mr. Trudeau can be an activist, too. Jagmeet Singh’s New Democrats offer him a dance partner. Mr. Singh will support him on pharmacare, national child care, pandemic relief, vaccination mandates, firearm bans and fighting climate change.

Mr. Singh is no Tommy Douglas, and Mr. Trudeau lacks Mr. Pearson’s greatness and gravitas – and that of his father, too. If Mr. Pearson remade the country, Pierre Trudeau saved it. Still, Justin can change Canada, too.

How? Embrace intercity high-speed rail, a national electricity grid and affordable housing, and make them national projects. Deliver clean drinking water on reserves. Build a national portrait gallery and a new national science museum. Address income inequality and the rural-urban divide. Oppose more decentralization. Drop the virtue signalling and hand-wringing. Hire a speech writer and offer a vision beyond sound bites and slogans.

Hell, if Mr. Trudeau is serious, let him use his authority as the most senior leader of the Group of Seven to lead an escalated global effort on the climate emergency. And let him find the resources to recommit Canada to the world, where we have become the gentle giant of gesture.

Having done some of this, Justin Trudeau will have crafted a durable legacy. It includes a price on carbon, the Canada Child Benefit, admitting Syrian refugees, renegotiating NAFTA, legalizing cannabis and modest Senate reform.

In 2024, after almost a decade in power, he can declare his work done. He can hand the party to Mark Carney, as Mr. Pearson did to Pierre Trudeau.

And then Justin Trudeau – an elder statesman in his early 50s – can step away. The pretender who blazed like a Roman candle across the Laurentian Shield can leave on his own terms, to the country’s applause, sadness or relief. Just like Mike Pearson.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this column suggested Mr. Trudeau should build a science museum. There is currently a Canadian Museum of Science and Technology.

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.